Insights

Lights, camera, action.

How to design a cinema: part 1.

It's a careful balancing act, optimising a movie theatre layout, whether it's a home cinema or purpose-built auditorium.

There is a wide range of aspirations and budgets for a cinema space, ranging from enthusiasts’ consumer-grade home cinemas through to purpose-built auditoriums with dedicated projection control rooms.

Our first port of call on any cinema project is to define a brief with the client to fully understand the aspirations for a space. With such a wide range of performance options, it would otherwise be very easy to over-engineer as well as under-engineer a solution.

Key early considerations which have a significant impact on a cinema design:

What is the intended capacity of the cinema?

The main deciding factor in the overall size of a cinema is the intended seating capacity. We must consider not only the intended quantity, but also the types of seating to be used – where rows of standard folding seats will obviously take up less space than luxury, reclining seats with side tables and extendable footrests.

What type of content will the space typically be used to display?

Defining the sources intended for display on the cinema system (cinematic content, film server, live TV screening, local inputs for presentations, games consoles, etc.) will inform key elements such as the optimal screen size and format (aspect ratio) to fit the space, and/or the requirement to support variable format content.

Will the space be used for commercial grade screenings?

This not only impacts requirements to meet certain standards of experiential quality for customers/users but will also dictate the choice of certain key technologies. Cinematic content distributed for commercial playback typically comes in an industry standardised, encrypted format which only a compliant cinema system will be able to play.

What aspirations are there for cinema audio?

The options for modern surround sound can range from a simple, standardised arrangement of loudspeakers (e.g. Dolby 7.1) through to fully immersive 3D surround sound formats (e.g. Dolby Atmos) requiring careful design with prescriptive requirements.

How will the space be operated?

We need to determine whether there needs to be a dedicated projection control room, a projectionist workstation or whether most functions can be automated/operated remotely or through simple user interfaces.

Often audiovisual systems are considered an add-on to a space, bringing extra functionality or enhancing user experiences. In most typical applications, audiovisual systems are designed, in this way, to fit the space provided. For example, a corporate meeting room may have a size, capacity and intended arrangement determined by the architect, and our role as AV consultants would be to recommend the correct type and placement of equipment to suit the space provided.

When it comes to cinemas, almost the opposite is true. The user experience provided by the audiovisual systems is the primary purpose of the space. As such, the spaces themselves must be designed to suit the cinema systems intended for inclusion.

One of our first considerations when looking at a new cinema is to assess the physical dimensions and proportions of a space for suitability. Working closely with the architect, our engineers will guide auditorium envelopes and arrangements to optimise user experience – occasionally leading to radical changes to sizes and shapes in early design stages.

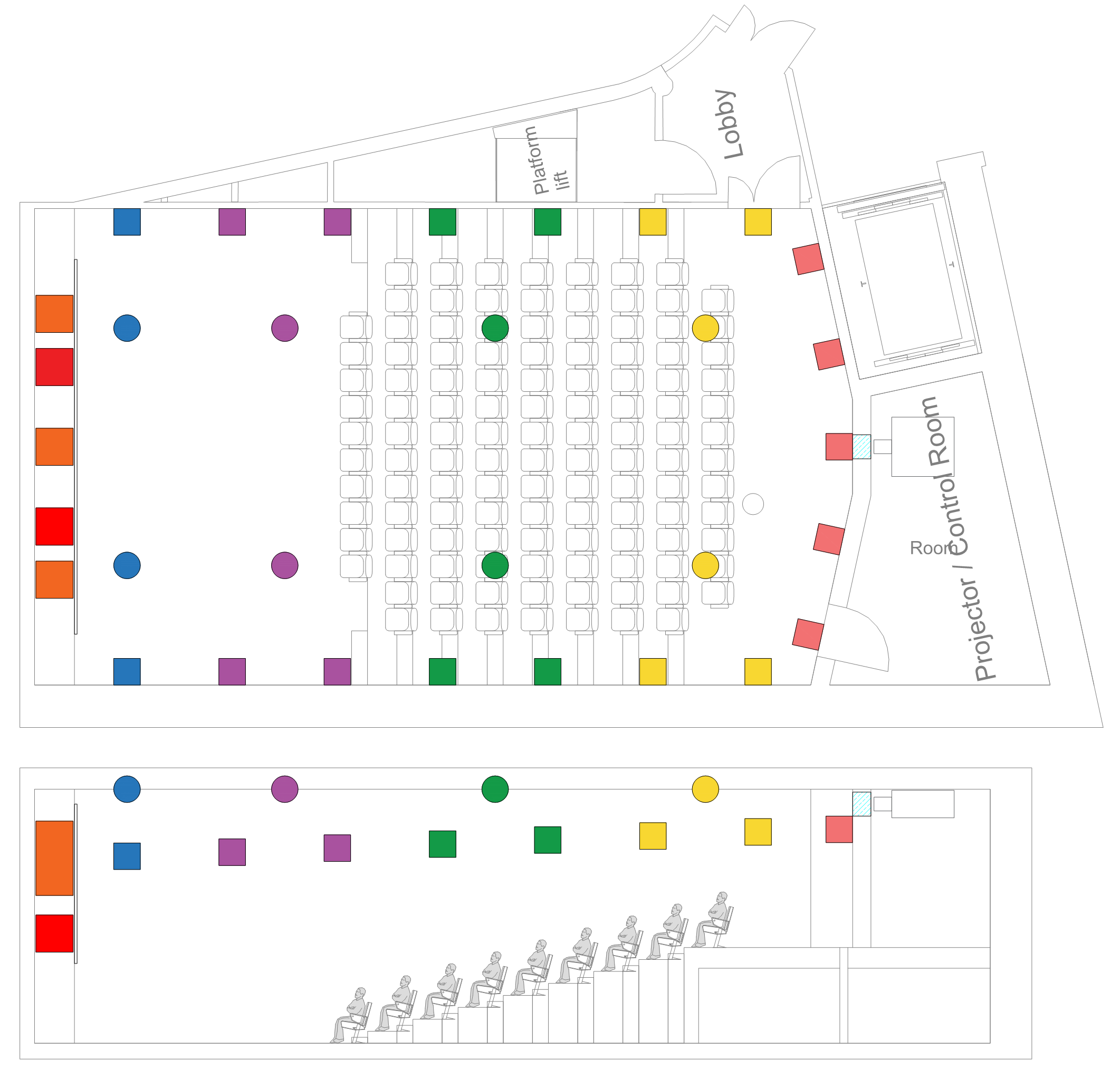

Theatre layout

When it comes to assessing a space’s suitability for use as a cinema, the key factors for consideration are centred around balancing the intended audience capacity with providing a reasonable and consistent viewing experience across the whole audience.

Seating types

Cinema seating options can be quite varied, even within the same auditorium, where customers may be able to pay a premium for a luxury comfort chair. The type of seating to be used may not be of utmost consideration in the early stages of a cinema’s design but will effectively define a potential audience ‘density’. This can have significant impact on a cinema’s potential capacity once the size of an auditorium has been fixed so it is important to understand client aspirations early on.

Figueras Smart RC ‘Standard’ seating and Figueras Hollywood ‘Executive’ seating

Video content format

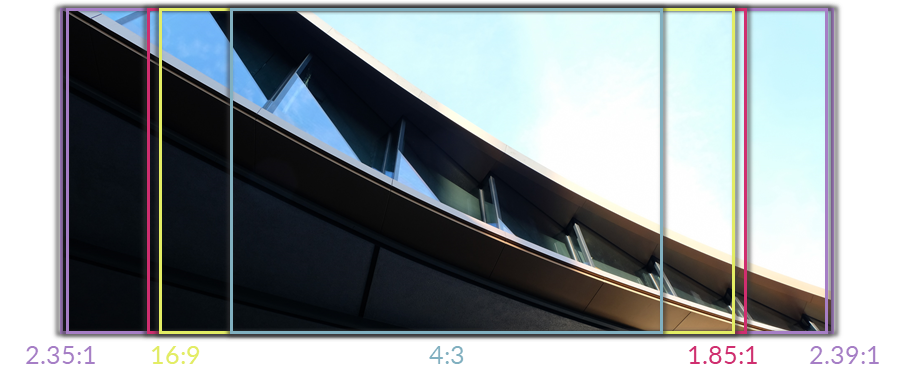

Video format is an important consideration for a cinema. Content, particularly cinematic, is/has been produced in a variety of standard (and non-standard!) aspect ratio formats over the years. Nowadays the main formats which would be considered are as follows:

- 4:3 Early standard television format

Sometimes referred to as ‘fullscreen’. This is generally considered obsolete nowadays; it was the standard format for old television, before the uptake of widescreen in the ’90s/’00s. However, this will still be used for playback of any older content (television or early film). - 16:9 Standard television format

This is the most common format outside of cinema and would be used for ad hoc presentations from a laptop or when using the cinema for any live TV events. - 1.85:1 Cinematic widescreen (flat)

Also commonly referred to as ‘flat’ in cinema, this is very similar to standard television 16:9. - 2.39:1 Cinemascope panoramic widescreen (scope)

Often referenced as 2.35:1, 2.40:1 (where historically standards have varied slightly), ‘scope’ is a commonly used cinematic panoramic widescreen format, traditionally shot using anamorphic lenses.

| Comparison of different cinematic video formats |

A typical cinema will include a projection/screen system which can flexibly support media in multiple formats (most commonly Flat and Scope). This may require the use of a variable masking system to automatically alter the screen to suit the aspect ratio of the content being presented at any given time.

An automated masking system comprises a motorised black curtain which trims the extent of the full screen surface either horizontally or vertically to achieve the correct screen shape. This is achieved through a process called ‘pillar boxing’ (horizontal trimming) or ‘letter boxing’ (vertical trimming) in a two-way masking system. Some systems may even include the functionality of both, resulting in a four-way masking system.

Viewing conditions

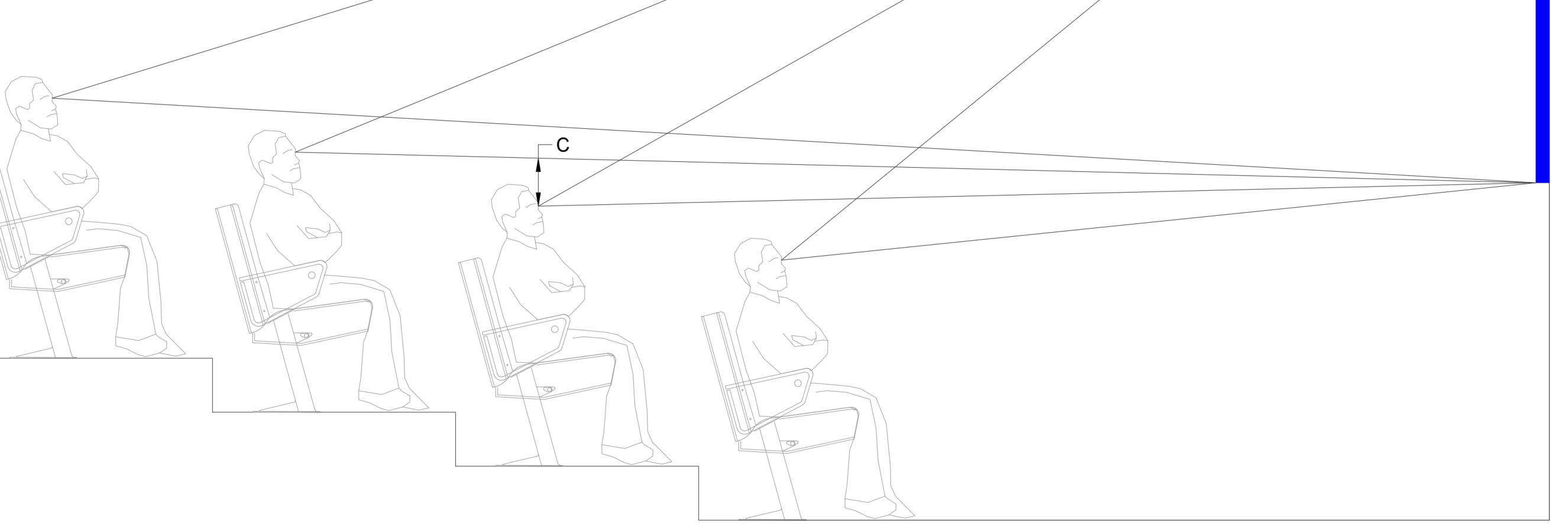

Given a requirement for a certain seat capacity, we produce ‘test-fit’ studies for different arrangements of screen size, format, and position. This allows us to assess viewing angles for audience members sat in different areas, as well as sightline clearance for rows having to view over the heads of those in front.

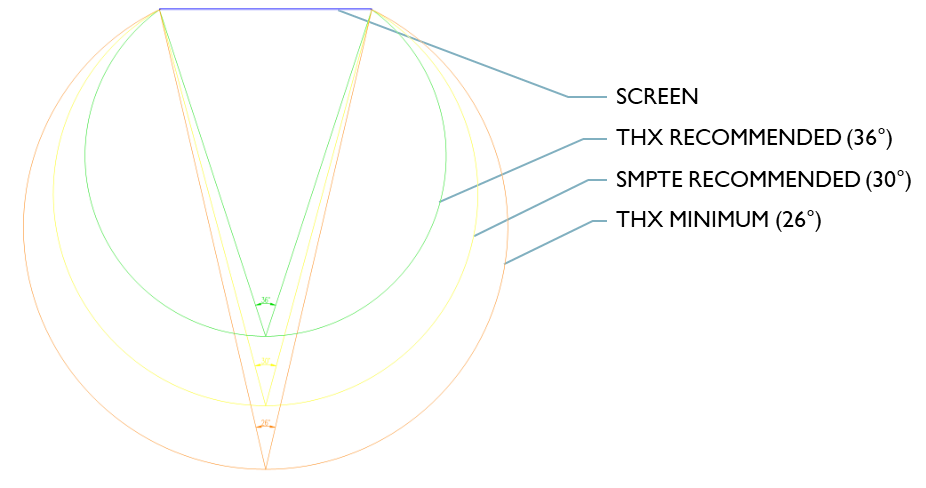

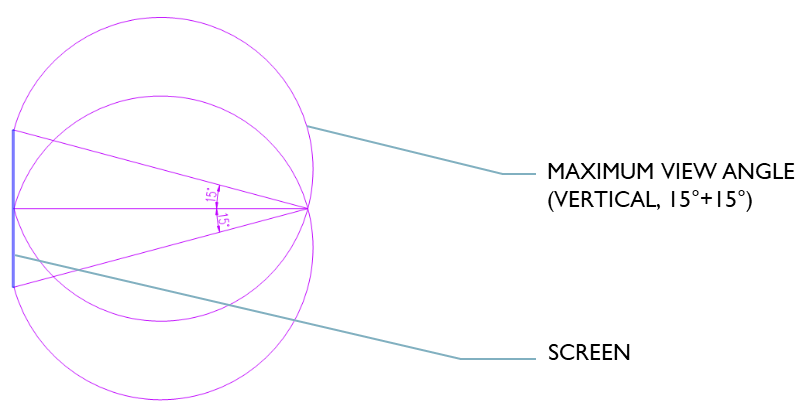

Quantifying viewing experience quality in the first instance comes down to defining acceptable viewing angle ranges and tolerances for sightline clearance. Often referenced for benchmarking viewing conditions are guidelines and standards defined by THX (the cinema standard pioneered by Georgy Lucas) and the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers (SMPTE).

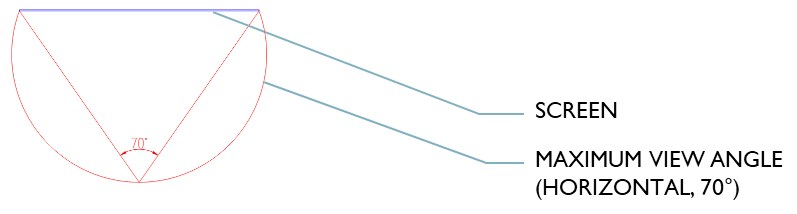

Ideal minimum limits for horizontal viewing angles are imposed to ensure that content can be seen clearly and legibly and to guarantee a suitable level of immersion for a cinematic experience.

Ideal maximum limits for vertical and horizontal viewing angles are imposed in order to avoid the screen from being overbearing or strenuous to watch – requiring constant head movements or uncomfortable neck craning to view all content.

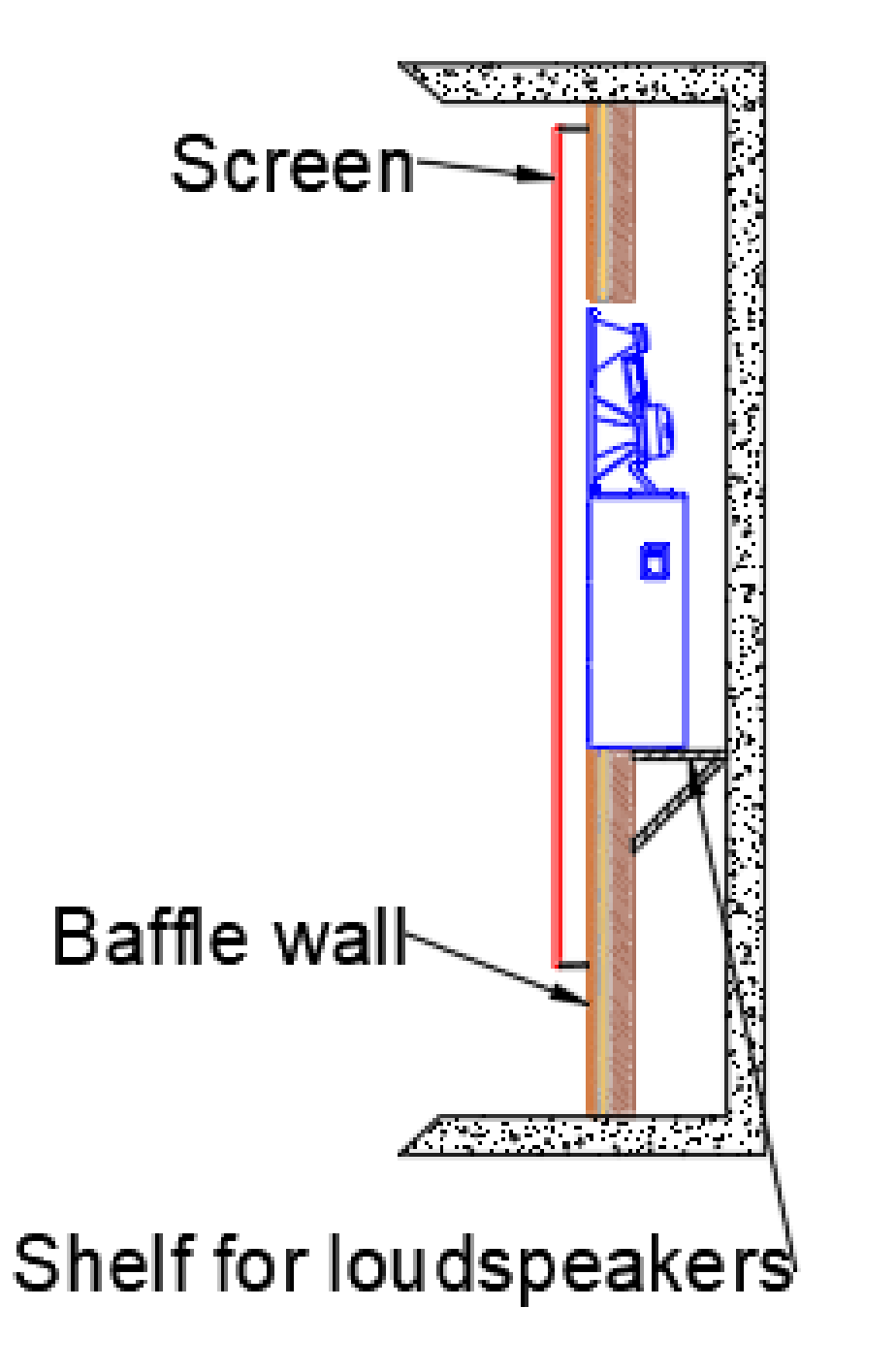

Sightline clearance is measured based on an assumed typical head position and eyeline level for each audience member. Cinemas almost always include a seating rake or stepped audience area to improve sightline clearance.

Insert C value table

Our test-fit studies can be used to generate easily understood mark-ups of a proposed cinema arrangement, showing the proposed seating spread across zones of ‘good’, ‘acceptable’ or ‘unacceptable’ viewing conditions, as related to the THX/SMPTE standards for context.

It is these mark-ups which we use to optimise the fundamental cinema layout with the architect, identifying common issues/considerations such as:

- Room too small for intended capacity

Usually typified by the front row(s) of seating being pushed too close to a large screen for comfortable viewing. Either the screen will be too small for those at the back, or too large for those in the front – not all audience members can be fit within the ‘ideal’ zones. - Room not tall enough

Where the ceiling is too low to allow an ideally sized screen to be placed at an appropriate height, or where the seating rake is too shallow for adequate viewing sightline clearance.

The ideal solutions to these issues involve relatively major alterations to the architecture through increasing the dimensions of the space and/or changing the shape of the cinema room. However, even when conducting these studies in the early stages of a project, there are usually other architectural constraints to consider, limiting what can be achieved.

Instead, compromises must often be reached with the client through either reducing capacity expectations, considering alternative seating options or accepting minor derogations to the viewing condition guidelines. This must be done with care, however. Minor derogations may be less than ideal but still acceptable, but major derogations will result in unusable seats.

Optimising a cinema layout is a careful balancing act focused around these core viewing condition measurements, but also considering many other factors. Often blindly addressing one issue can inadvertently create problems elsewhere.

For example, where sightline clearances are too low/unacceptable, one solution would be to raise the level of the screen. In doing so, the vertical viewing angles, particularly for those in the front row(s), may become unacceptably steep if pushed too far. Another solution would be to increase the seating rake, but this may lead to architectural issues or introduce a risk of people on the back row(s) blocking the projection beam (causing shadowing).

Equipment accommodation

While keeping these room properties in mind, the core operation of a cinema also hinges around the successful integration of all the necessary audiovisual equipment. Much of the equipment associated with cinemas can be bulky and require specific placement in order to perform. Architectural allowances must be coordinated at an early stage, even before specific equipment has been selected, in order for us to feel confident that everything will fit.

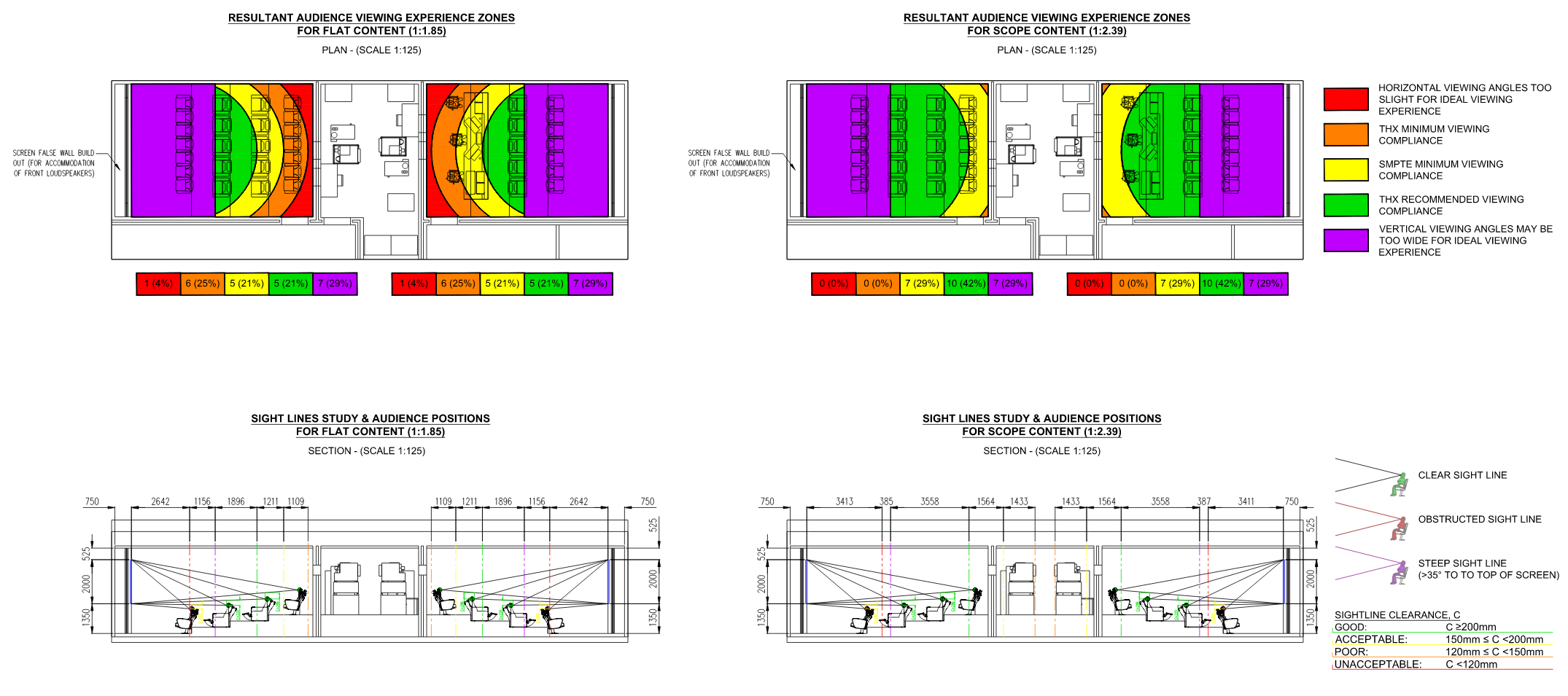

Baffle wall

Most cinema designs will, regardless of the audio format, include main LCR loudspeakers (front channel left, centre and right channels) which will need to be positioned in line with the screen itself. This is so that the acoustic image for the main cinema content will sound to the audience as though it is coming from the screen.

For this to be practically achievable, the LCR loudspeakers need to be positioned directly behind the projection screen surface. What this requires practically is for the screen surface to be built onto a bespoke baffle wall build-out, the cavity behind which can accommodate the screen loudspeakers on plinths or shelves.

| Indicative LCR loudspeaker mounting within acoustic baffle wall |

The screen itself can then be mounted to the front of the baffle wall construction, with care given in the specification to ensure the screen material is effectively acoustically transparent.

The depth of a baffle wall void can be variable, depending on requirements for accommodating different loudspeaker depths or access considerations. The decided upon off-set of the screen from the cinema envelope back wall must then be factored in to viewing condition assessments, where the screen will be pushed closer to the audience.

Often other details are built into the baffle wall including cut-outs for subwoofers, or access panels for maintenance of the loudspeakers.

Projection booth

Usually the largest piece of equipment to be integrated into a cinema space is the projector itself. The projector must be installed such that the projection beam reaches the screen without distortion. While some image offset can be achieved with projectors, this generally means that the projector must be installed in a very specific location relative to the screen, with strict tolerances. With the exception of smaller home cinemas, this usually means dedicating a space off of the rear of the main auditorium to use as a projection booth.

In addition to the projector, a dedicated booth can also be used as a working space for a technician and accommodation for all other cinema equipment which does not need to be physically installed within the auditorium. Bulky media servers, controllers, audio processors and amplifiers can add up, using a lot of space; a typical cinema system usually requires at least one full-size 19” equipment rack, sometimes more!

Projector units and rack-mounted equipment usually mean a lot of noisy cooling fans. A cinema is to be considered a highly sensitive space for unwanted noise break-in, so a projector booth also provides an opportunity to acoustically separate noisy hardware with a physical partition.

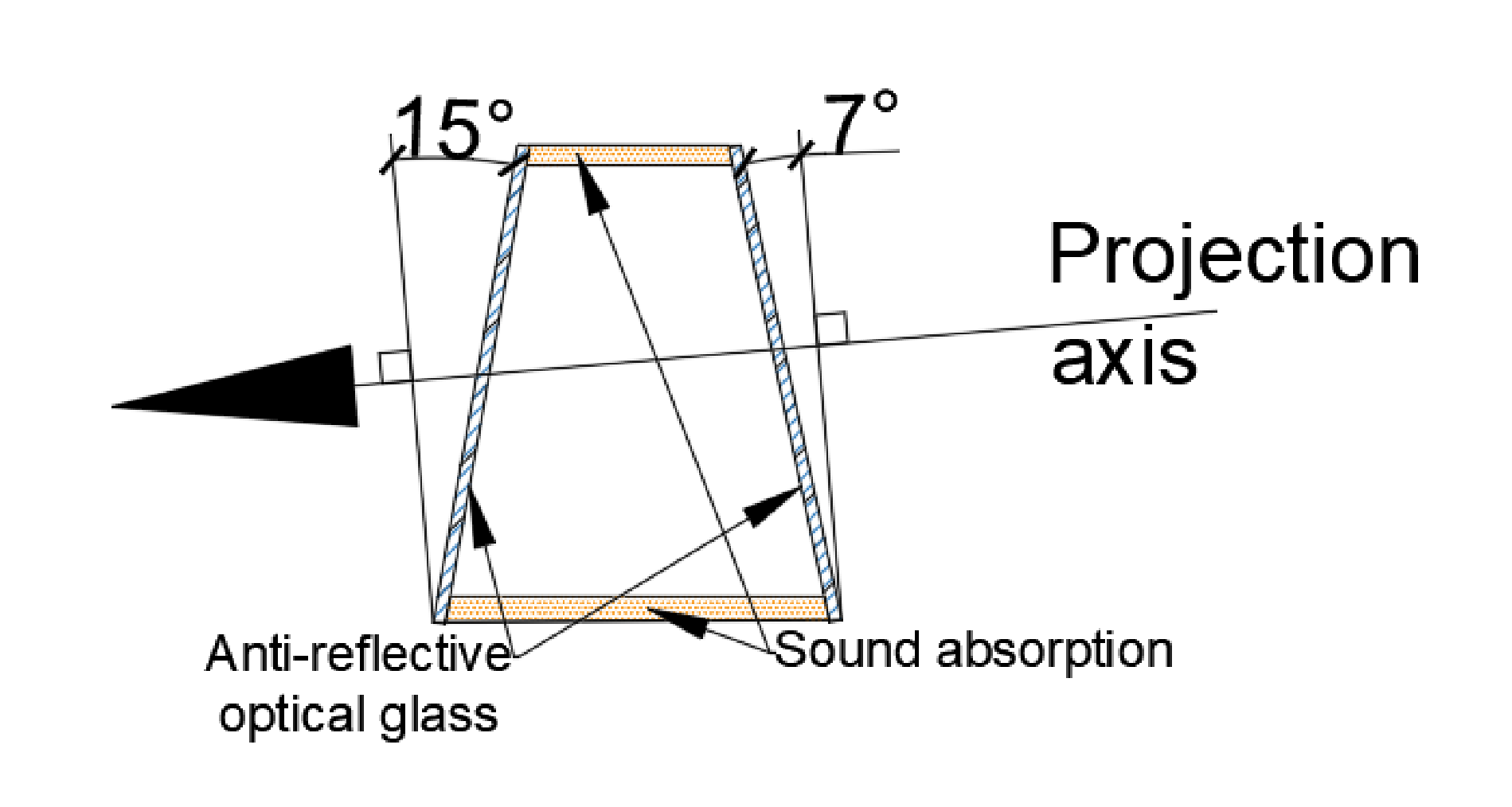

In order to shine a projection beam through into the cinema, while maintaining this important isolation, specially designed projection porthole windows are required to provide high acoustic insulation performance without interfering with the projected image.

| Typical projection porthole construction |

In some cinemas, additional porthole windows are also required for a projectionist or operator to view the auditorium from the booth. In any case, proposals must be properly considered so that any window is fit for purpose without compromising the partition performance.

Audio system: finding that sweet spot

A core part of an immersive cinema experience is the provision of high-quality multi-channel audio playback. Clear audio playback across a wide dynamic range allows for quiet, intimate scenes to be audible and intelligible while also allowing louder, intense action scenes to have the proper impact.

Multi-channel surround sound, where audience members can localise different elements of a film soundtrack from different directions, improves this immersion further and is a must for any cinema application.

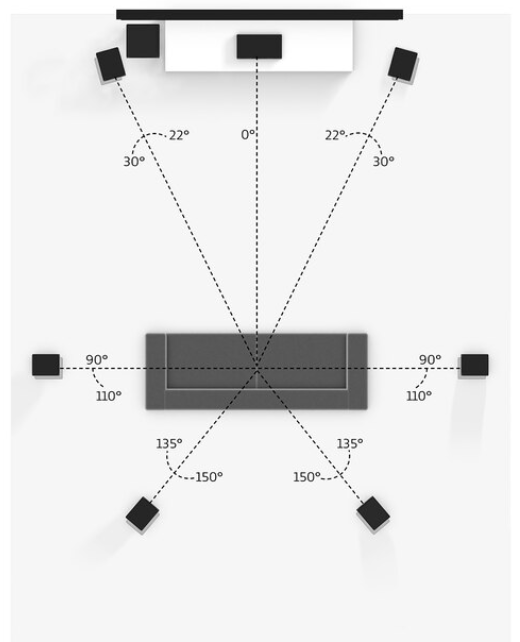

Traditionally this has been achieved using prescribed cinema surround sound formats where loudspeaker positions are pre-determined. Specifically mixed down channels of audio are produced for a film to be played through loudspeakers in particular positions around the auditorium. An example of this most people are familiar with is Dolby 7.1 where the notation refers to there being seven main channels of loudspeaker (front left, front centre, front right, left, right, rear left and rear right) and one LFE (low frequency effects) subwoofer channel.

The speaker placements for these traditional formats up are quite specific, where the intention is that the cinema auditorium is exactly replicating the arrangement in the studio where the film sound track was mastered. The localisation effect of surround sound elements from traditional formats in this way tends to work best for audience members within a ‘sweet spot’ in the middle of the audience, where the conditions of the mastering are most accurately represented. For large audience areas, surround sound image localisation can be warped for audience members on the edges of the seating area, farthest from this theoretical sweet spot.

An example Dolby 9.1 layout is shown in a sketch below.

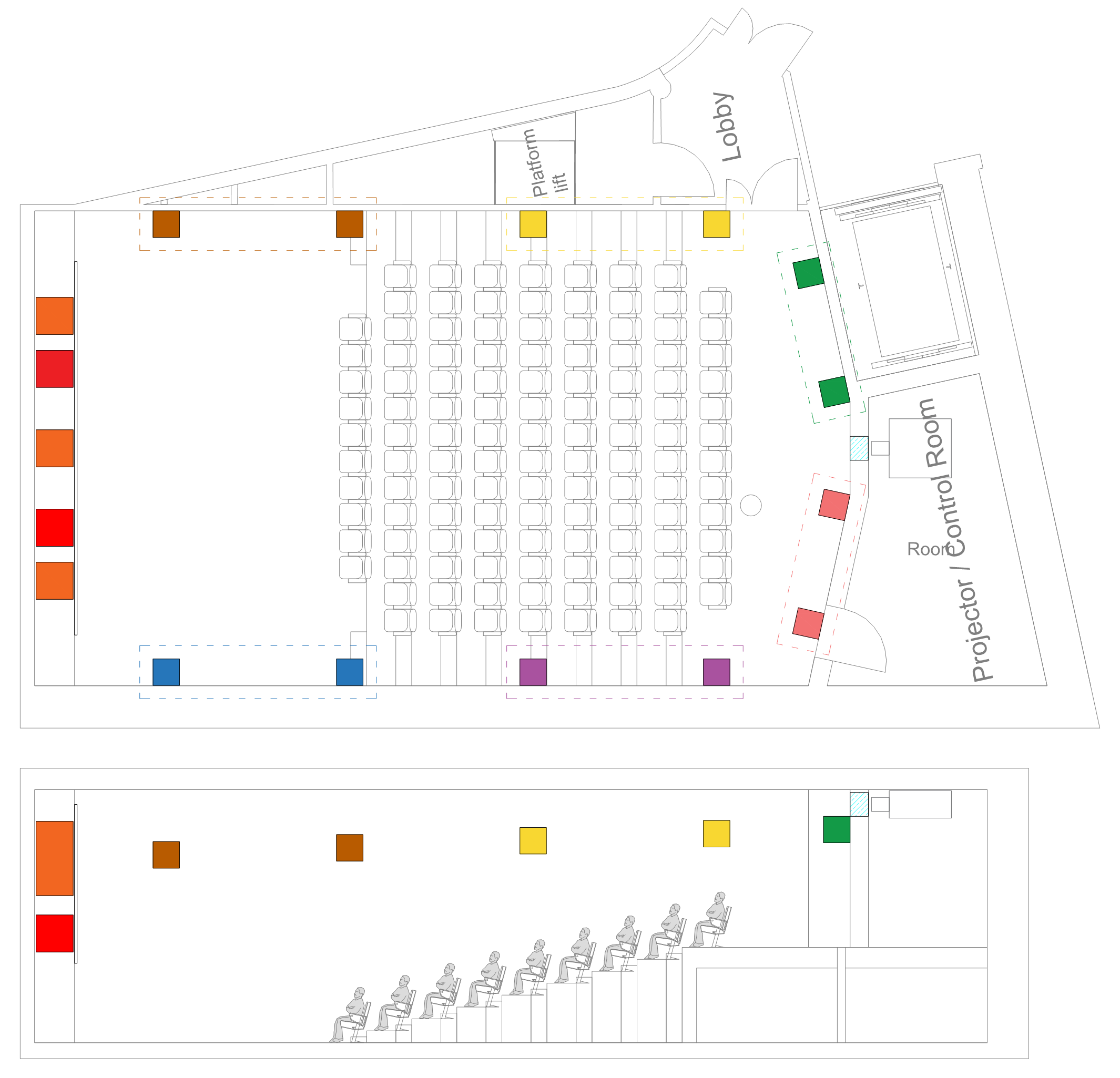

A more modern approach to surround sound technology is to use object-oriented sound processing (e.g. Dolby Atmos/DTS:X/Barco Auro3D). Instead of pre-rendered loudspeaker channels, a film sound track will have sound ‘objects’ (a track or stem) with a programmed position or trajectory. A cinema audio processor will then interpret this information and use the loudspeaker set-up specific to that exact auditorium to replicate the intended acoustic effect with level differences and time alignments between loudspeakers.

This requires a system to be calibrated specifically to an auditorium, but it will achieve much better results, emulating a surround sound field for all audience members (not just those in a sweet spot). Due to the nature of the algorithms, surround sound effects are also no longer confined to a two-dimensional plane across the audience. The addition of ceiling loudspeakers is used to create more realistic and complex three-dimensional sound fields with ‘height’ channels allowing objects to pan over head, as well as around the sides of the audience.

With an object-oriented system, loudspeakers no longer have specific channel assignments; the processors will simply optimise the output for the loudspeakers and placements available. In theory this simply means that the more loudspeakers that are included the better, however guidelines on ideal lousdpeaker placement and spacing still exist.

An example layout, based on the Dolby Atmos Specification, with colour-coded zones/regions, is shown in the sketch below.