Insights

We need to talk about ALAN.

The impact of light pollution.

Artificial Light at Night (ALAN) could be threatening our biodiversity and academic evidence paired with recent news coverage is strengthening these concerns.

One paper has cited that 1 million species, including up to 40% of insects, could go extinct within the next few decades. While other societal events have contributed the decline (increased urbanisation, land change, pesticides, climate change etc) ALAN has rarely been considered as a cause.

Understanding ALAN.

Artificial Light at Night is an inevitable consequence of modern life. Light supports our 24-hour society and allows for 20th century living.

But…light itself is not the problem. When light is used poorly and inappropriately it impacts ecological activity and night-time environments.

The wider impact.

Poorly managed light is a detriment to all ecosystems.

Under the sea

Marine and aquatic life are affected. The biomass of algae has been seen to decrease with simulated light spills. Fish, amphibians and sea-mammals can also be disorientated by light shining in to into rivers and seas.

In the sky

Bats are often associated with light pollution and are subsequentially a protected species in the UK. They play a vital role in controlling our insect populations, consuming approximately 1200 insects per hour. ALAN can disrupt their feeding times through delaying their emergence from roosts.

From the ground

The growth of trees and plants are impacted by daily and seasonal changes in light. Their shedding, flowering and even direction of growth can be unnaturally affected by light at inappropriate times.

Closer to home

ALAN doesn’t only effect flora and fauna, it also effects the human population.

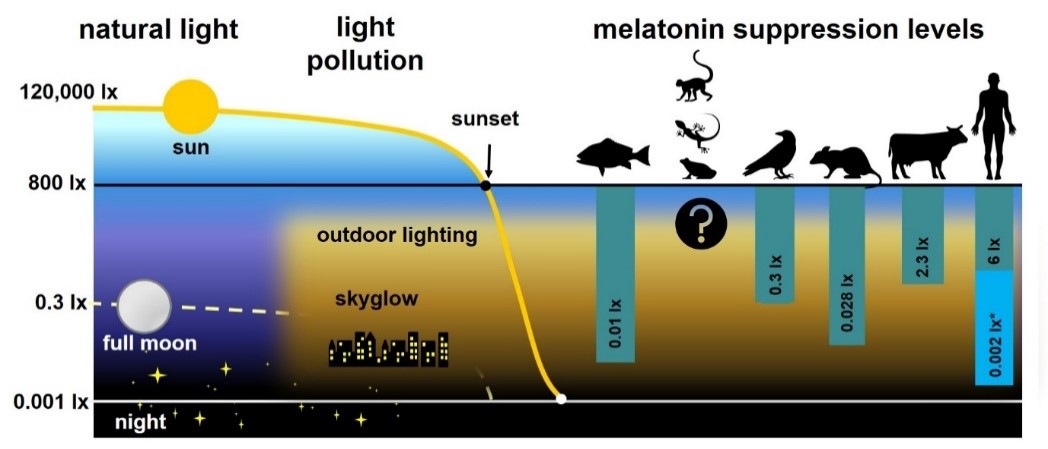

Light at night can have significant physiological impacts on our own circadian rhythms.

The connection between light and well-being, sleep and time-clocks is well known. We know that if light delays or reduces our sleep quality, there can be serious health implications.

Academic research in this field is growing too, with evidence suggesting that light is a trigger for the release or suppression of melatonin.

A new phenomenon?

Light pollution, skyglow, glare and light trespass have been classed as statutory nuisances in the UK for many years. However, there has been a recent increase in awareness and interest into the subject.

People understand ALAN’s environmental impact and the potentially catastrophic effects it could have on our ecosystem.

Cause and effect.

Where did this problem start?

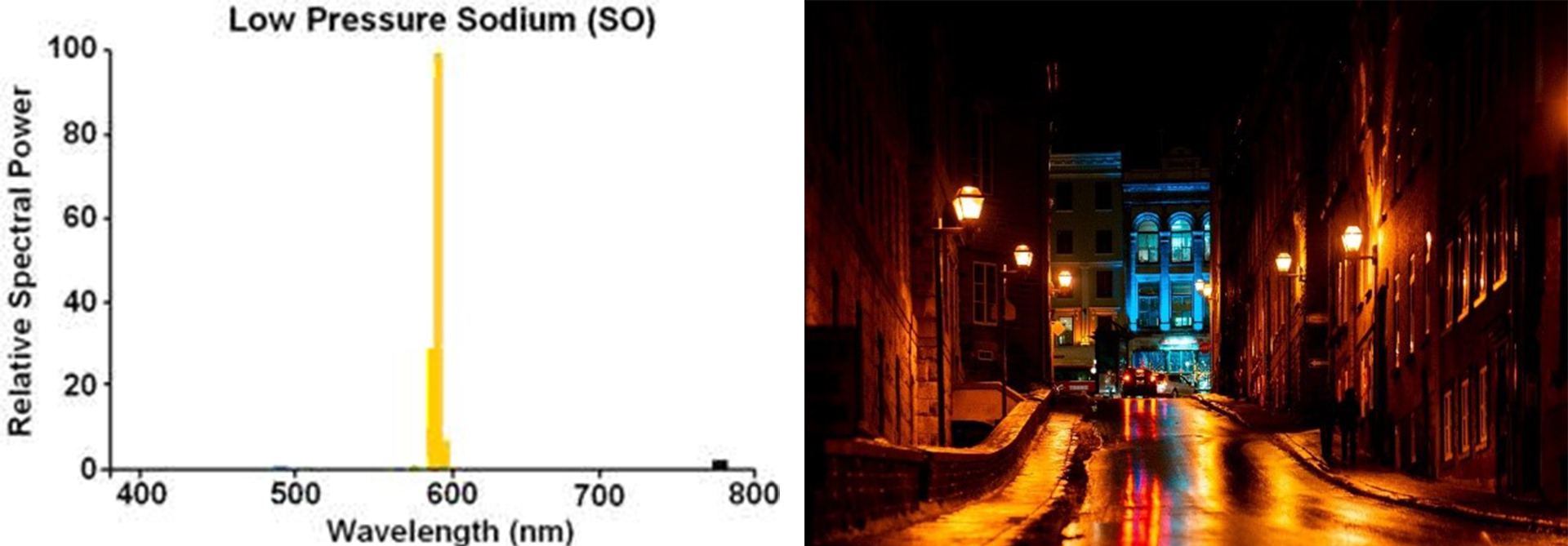

Old streetlights were low pressure, sodium lamps with an amber appearance and a single spectrum wavelength. Astronomers accepted their used as they could still see the night sky and they had a low impact in terms of melatonin suppression.

But…as the bulbs were low energy with a negative colour rendering, they became synonymous with poorly illuminated, intimidating streets.

The subsequent development of LED caused a major change to light pollution.

The old soft, low impact sodium lights of the past were replaced with cool, white, blue spectrum bulbs that are associated with night-time safety.

Increased urbanisation saw harsher LED light placed into greenfield areas and developing parts of the world, so our towns, cities and rural areas got brighter.

The biophilic impact.

The transition from sodium to whiter light sources happened over many years.

The effects on environment are known, but some argue that we may have lost something which is equally important; the views of our stars.

The biophilia hypothesis indicated that humans have an innate tendency to seek connections with nature and other forms of life.

While biophilic design has seen the addition of green walls and plants added to offices, people rarely speak about our connection with the stars.

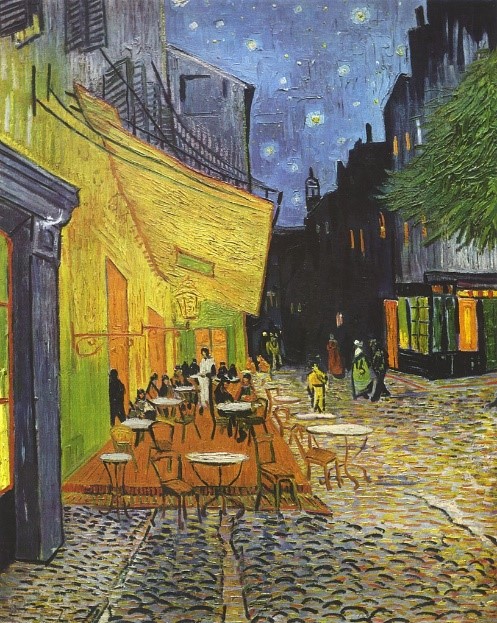

For example, in his 1888 painting ‘Cafe Terrace at Night’, Vincent Van Gogh showed the night sky as the ceiling to his composition. Bright stars are visible against the juxtaposition of the warm glow from the café lighting.

But, in contemporary external environments, the proliferation of lighting equipment means that this view is often lost, with the stars no longer seen. ALAN can remove the top third of our composition, halting our access and connection with the universe.

What can we do?

To protect our environment and night sky, we need to see a step-change in the use of ALAN.

For urban design we need to start questioning the necessity of illuminating a building façade or the need to light streets all night and…

…we need to put the ecosystem that sustains us at the forefront of our external projects.

Modern lighting design can make this possible.

Installations should be approached with a considered framework of social and environmental responsibility. This allows the beauty and poetry of a beautiful outdoor environment to be seamlessly blended with vibrant, kinetic and interactive lighting.

Dim it down.

One of the great advantages of LED technology is the ability to dim and this will eventually become ubiquitous in the streetscape. Through innovative technology, towns and cities of the future will be able to safely and sustainably light their streets.

Streetlights could be reduced or switched off at curfew times and then relight when a presence is detected. The lights could also seamlessly change from white to the less impactful amber at allocated times or densities.

In the not too distant future, we could see lighting equipment sensing our presence through our smart phones, anticipating our route and preparing our street lighting.

Looking ahead.

While light pollution is a contemporary consequence, we need to start considering its impact as all stages of project work.

As a design and construction industry we spend a lot of time considering humans or people centred design but, given the ecological catastrophe we face, but maybe putting ourselves at the pinnacle of focus is the root of the problem?

Now is the time to consider ECO-Centric design where the ecology and biodiversity of the planet is considered equally with the needs of humans.