Insights

The delicate art of daylight balance.

More isn’t always better.

Mounting evidence is demonstrating the importance – and benefits – of designing buildings that are primarily illuminated by daylight.

However, like any aspect of functional design, daylighting requires a delicate balance to ensure it works in the best possible way.

Our wellbeing suffers at both ends of the scale; too much daylight can be just as harmful as not enough.

Our love affair with glass in architecture shows no sign of abating, but copious glazing brings glare and overheating, leading to heavy shading elements and closed blinds over entire facades. Inefficient shading can result in the oft-documented “blinds down, lights on” syndrome. This is bad for both energy consumption and occupants’ health and wellbeing.

Smart shade.

Automated dynamic shading avoids this problem by only being closed when necessary, thereby maximising the benefits of daylight for occupants and energy efficiency. However, the major downside of these solutions is that they often carry a maintenance burden. Equally, research has shown that, if occupants are unhappy with how they are controlled, they often take matters into their own hands (such as covering or disabling sensors) and undermine the energy efficient intentions of the design.

In contrast, smart glazing materials, such as electrochromic glazing, can change opacity in response to daylight conditions.

Smart glazing is one of the most exciting recent developments in the science of shading as it delivers a dynamic façade without the mechanics.

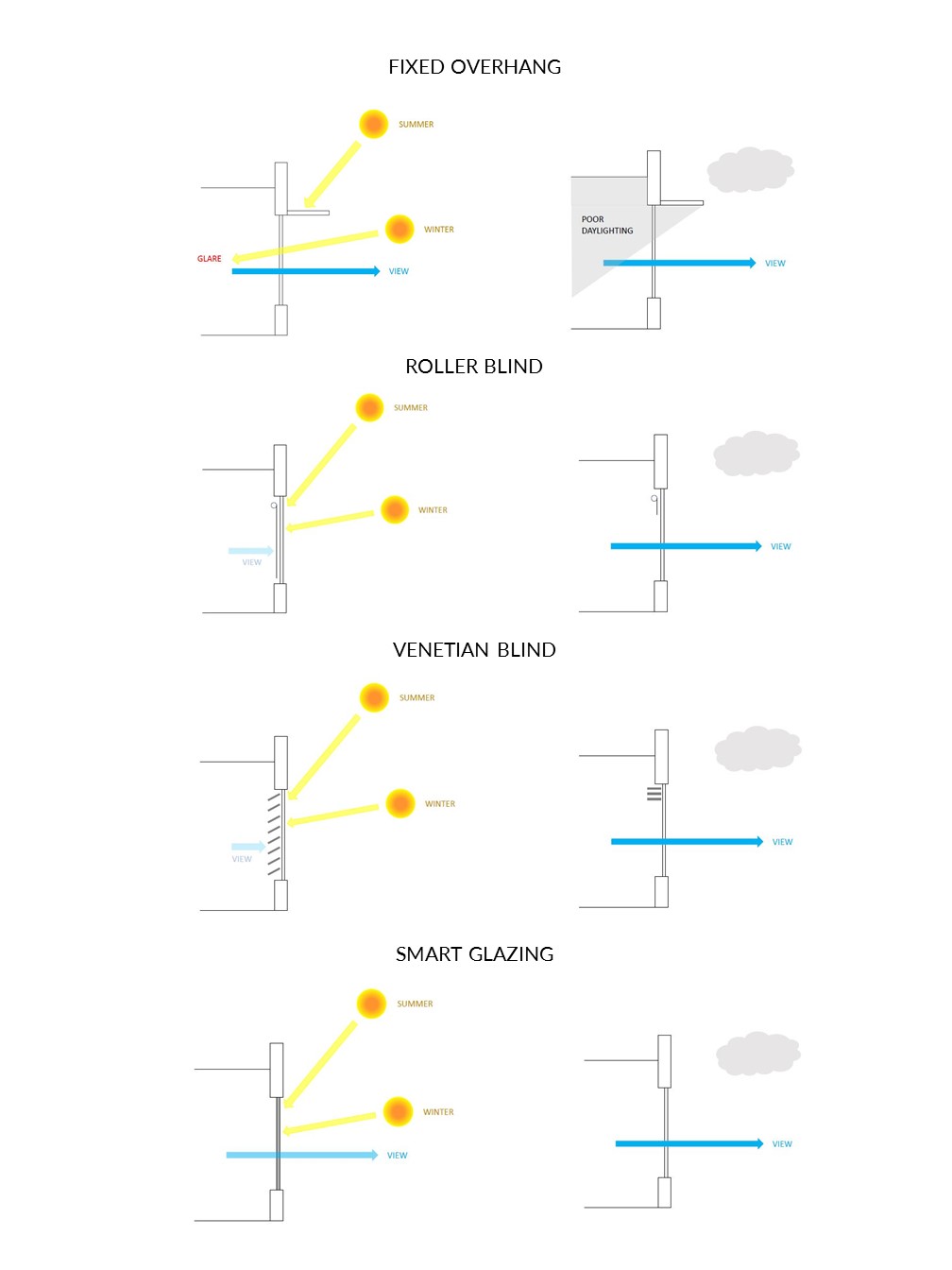

Like any solution, they need to be carefully considered and analysed against other options (as shown below) and are by no means a panacea.

User-centred solutions.

So how can we control daylight without losing the benefits? Designing buildings in a way that is conscious of the prevailing solar characteristics of the site is a good start. But even then, some moveable shading elements are usually needed for occupants to be comfortable. Furthermore, in workplaces where occupants share open-plan areas (and may be constrained in how much they can change their position), providing adequate daylight control can become a complex task.

Crafting the right solution requires an understanding of occupants’ needs, and does not have to involve technologically sophisticated facades.

Solutions can range from simple manual blinds to highly engineered facades. The key is in recognising which approach meets the needs of occupants, the aesthetics of the building, and the need to minimise energy consumption. Arguably, the overriding need is that of the occupants: if a building doesn’t work for them it has failed immediately.

Whether the solution is high or low-tech, the key is in thoughtful application. For example, if manual blinds are used, can occupants easily reach the controls? If not, how is remote control going to be provided? The answer depends on many factors, such as how many people will occupy the space, what their needs are, and whether they have a sense of ownership of the building. Understanding occupant behaviour around shading and visual comfort is key.

Regardless of the solution, the challenge remains the same: finding the best way to control daylight without cutting ourselves off from its many benefits.